It’s a Tuesday near the city of Dolores, western Uruguay, where a huge machine known as “Mosquito” moves through a green soy field. Its giant arms, which stretch out like the wings of an insect, were designed to spray chemicals on the crop.

But now they have a different function.

Uruguayan researchers have adapted the machinery to release capsules containing wasp eggs, which on hatching will fight pests and reduce the need to use agrochemicals. They are deployed on a field planted with non-genetically modified soy.

Soy is Uruguay’s main crop. The country has planted one million hectares of genetically modified soy (GMO) and around 11,000 hectares of non-GMO soy. Most of GMO produce is exported to China, where they use it to feed pigs and chickens.

China imports around 90 million tonnes of GMO soy each year and consumes 15 million tonnes of non-GMO soybeans, most of it produced in the country.

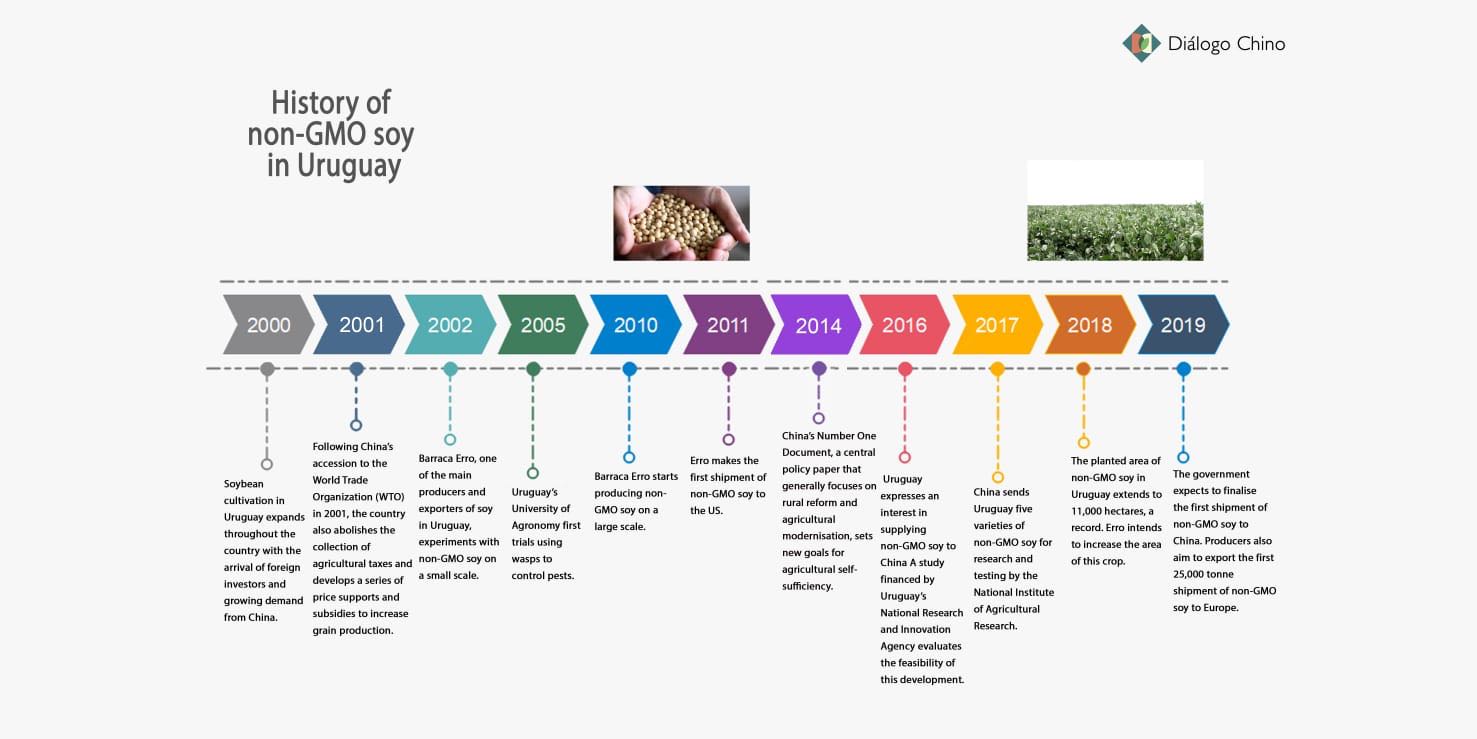

Years of dialogue

The Uruguayan government expects the country to make its first shipment of non-GMO soy to China this year, a possibility that has been years in the making, Enzo Benech, Uruguay’s minister for Livestock Agriculture and Fisheries (MGAP), told Diálogo Chino.

“Uruguay can be a reliable supplier of soy for human consumption for China and offer guarantees. It is an opportunity for the country,” said Diego Montes, general director of Agricultural Services at MGAP. Non-GMO soy is consumed in China in products such as tofu and soy sauce but it does not currently buy from Uruguay.

In 2016, Uruguay made firm efforts to explore the possibility of exporting non-GMO soy to China, said Montes.

The following year, five varieties of non-GMO soy arrived from China. The National Institute of Agricultural Research (INIA) assessed their quality, protein and oil levels, aiming to then grow them and sell them back to China.

More money for distinguished products

Due to its size, Uruguay cannot compete with the volume of soy produced by Argentina, Paraguay or Brazil. So the government hopes Uruguayan soy will stand out for its quality.

Sergio Ceretta, director of INIA’s Dry Land Cultivation Program, said: “We are putting a lot of emphasis on quality and characteristics. We want to target the soybean market for human food in China, beyond what we sell to them today.”

Some markets are willing to pay more depending on production methods. Uruguay is paying attention to market signals in order to produce what the world demands and might be willing to pay a premium for, Benech said.

Ceretta believes China may be willing to pay more. Yet prices are still uncertain for non-GMO compared to the more heavily-traded GMO variety.

Wasps, soy and agrochemicals

Producers looking to profit from this premium are now using “biological controls” to combat pests rather than chemical pesticides.

Uruguay has experimented with these biological controls since the beginning of the 20th century. Insects were introduced from abroad to act as natural predators, mostly in a controlled way so as to not alter the local ecosystem.

1940

the year chemical pesticides were introduced in Uruguay

However, with the emergence of chemical insecticides in 1940, the development of natural pest controls was almost entirely put on hold.

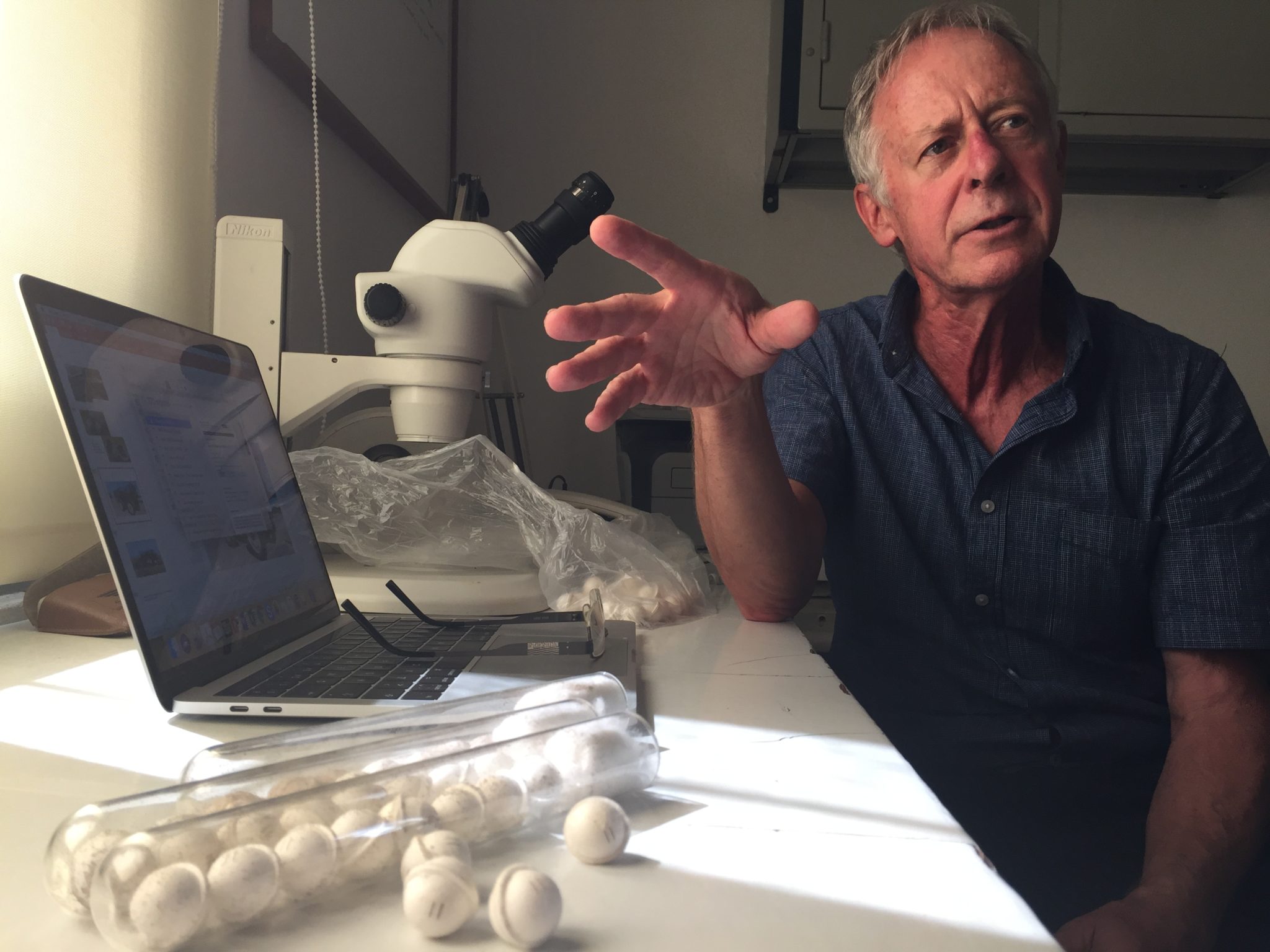

César Basso, a professor at the University of Uruguay, investigated using a small wasp less than half a millimetre in size to control a larva that affects sugar cane. That same species of wasp is used today for soy pest control.

The process is non-toxic but it does require costly, dedicated laboratories.

Use with soy began on a very small scale in Uruguay in 2005, when a group of researchers placed small paper sachets containing wasp eggs, one by one, near crops.

The capsules distributed by “Mosquito” contain egg parasitoids – insects that live close to a host species it eventually kills. They spread in summer as high temperatures help hatch the eggs in a few days.

The introduction of wasps in the cultivation of soybeans helps combat plagues of crop-munching caterpillars. French company Bioline joined the project years ago and carried out tests on 1,800 hectares of non-GMO soybeans. The practice could extend to GMO crops.

Basso said the results are very encouraging and hopes to expand cultivation using the technique. Barraca Erro, the only non-GMO soy producer in Uruguay, wants to continue with the experiment.

Challenges

The project still faces challenges, namely the time-consuming and expensive nature of production.

In 2018, Uruguay requested the product specification needed to sell soy in China, which asks for guarantees that it is pure and uncontaminated by GMO crops.

To be able to go out into the world to compete with soy for human consumption, you have to give guarantees

Soybean produced in China is basically non-GMO. The National Grain and Oil Information Centre predicts that within 20 years the planted area in China will reach 8.47 million hectares.

Chinese companies are also planting 100,000 hectares of non-GMO soy in Russia, which are expected to supply millions of tons of non-GMO soybeans over the next five years. Around 20,000 tonnes of soybeans harvested will be transported back to China, with a value of US$6 million.

The question of whether GMO soy is safe for human consumption has been controversial in China. TV personality Cui Yongyuan has campaigned against GMO food since 2013.

In October last year, provincial paper the Heilongjiang Daily published an article quoting an industry insider as saying: “In recent years, China’s top scientific, medical and military medical research institutes have come to the conclusion that GMO soy is unsafe.”

National media questioned its veracity. Yet, as uncertainty over its safety continues, non-GMO soy dominates the domestic food market.

Montes said the traceability of soybeans “from sowing to shipping” is a key element in the quest for quality, something that Uruguay has experience with as its meat industry traces cows from pasture to plate.

“To be able to go out into the world to compete with soy for human consumption, you have to give guarantees,” Montes said.