After over a decade away from Brasília, the celebrated environmentalist Marina Silva will find a very different capital from the one she left behind, when she returns as a federal deputy next year. After her election earlier this month, she is also tipped to return to her former position at the helm of the Ministry of Environment, should Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva pip Jair Bolsonaro to the presidency in the second-round runoff on 30 October.

58%

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon fell by 58% between 2004 and 2007, under the guidance of Marina Silva in her former role as environment minister

Marina Silva served as environment minister between 2003 and 2008, during Lula’s previous presidency (2003-2010), a tenure which saw Brazil become a world leader in the creation of protected areas, while deforestation in the Amazon fell by 58% between 2004 and 2007. Silva then stayed three further years in Brasília to finish her mandate as a senator.

Since then, she has sought to tread her own path in politics. In 2013, she founded her own party, the Sustainability Network (REDE), before contesting three presidential elections, running against the Workers’ Party of which she was a member for over two decades. But on 12 September, the tide turned, as Lula and Marina publicly announced their reconciliation.

“Politically, there were – and are – divergences,” she told Diálogo Chino. Nevertheless, she was clear that the risk of a second term for Bolsonaro required broad alliances. “We have reached a situation where it is either democracy or the end of democracy.”

Silva said that despite their political distance, she and Lula – who share similar backgrounds of poor childhoods and struggles in social movements – had never stopped talking. During their reunion, which had been sealed earlier in private, she handed him a list with 26 commitments to “rescue the lost Brazilian socio-environmental agenda”.

In the document later released to the press, Silva calls for the restoration of technical staff and budgets at environmental agencies, including the Ministry of Environment, which have been dismantled during Bolsonaro’s administration. Among other actions, there are also demands for the resumption of plans to prevent and control deforestation of the Amazon and Cerrado, something created during her time as minister, as well as the encouragement of low-carbon agriculture.

She is confident that her proposals will be taken forward by Lula, should he win the presidency: “On that day of the twelfth, the former president made a public commitment saying that the Brazilian environmental agenda will be transversal, and that it will be at the highest level of priority.”

Minister once more?

Marina Silva seems the most obvious candidate to assume the post at the environment ministry in a potential Workers’ Party government. But when asked if she would accept the position, she refused to comment: “At this moment, no presidential candidate should be talking about a ministry. And no one who supports a candidate should be thinking about a ministry.”

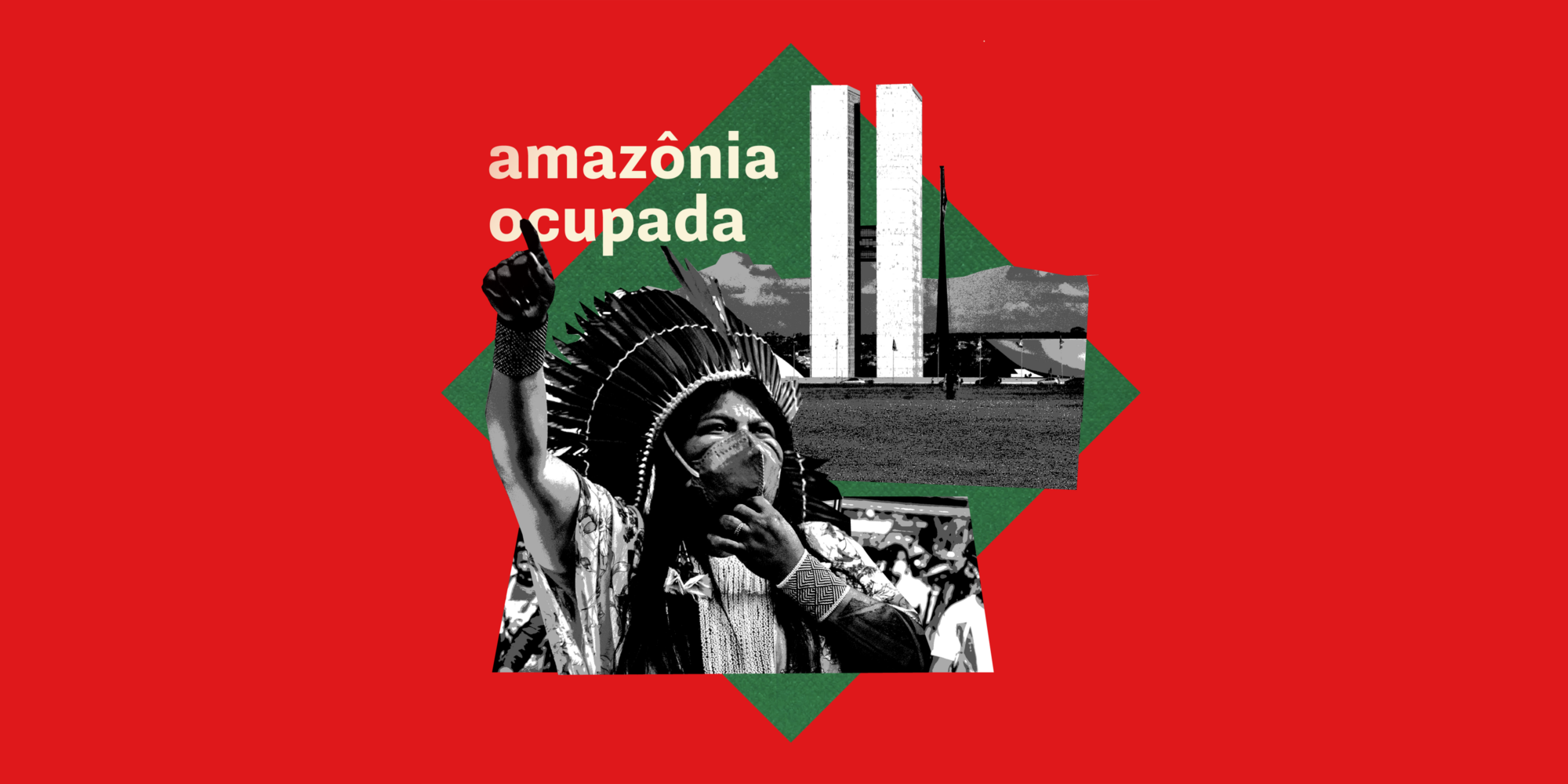

Whether as federal deputy or minister, the environmentalist will face a congress that, as current affairs and culture magazine Piauí defined it, is “more hostile to the environment”, starting with the recent election of Ricardo Salles, a former ministry head under Bolsonaro. Even after resigning from his post following accusations of involvement in the illegal logging industry, he will return to Brasília as a federal deputy with almost three times more votes than Silva.

At this moment, no presidential candidate should be talking about a ministry. And no one who supports a candidate should be thinking about a ministry

Meanwhile in the senate, there is a return for Bolsonaro ally Jorge Seif Junior, a former agriculture and fisheries minister who, according to The Intercept, changed fishing sector regulations to benefit his family. And back in congress, Zé Silva, author of a proposed bill that could boost land grabs, is back.

Joênia Wapichana, previously the only indigenous leader in Congress, was not re-elected, but indigenous leaders Sônia Guajajara and Célia Xakriabá won their first election.

Environmentally minded politicians who set foot in Brasília in 2023 will find a Brazilian landscape transformed by years of record-breaking fires and deforestation, driven by the advance of agriculture and cattle ranching, and of mining on indigenous lands; and by heatwaves and drought in areas of agribusiness. These present situations that will be difficult to reverse in the short term, even though climate targets taken on by the country are already knocking at the door.

No plain sailing for a Lula government

Struggles could even come within a potential Lula and Workers’ Party government. “The divergence of Lula and Marina was representative, and very profound,” explained Natalie Unterstell, founder of Política por Inteiro, which monitors environmental policy in Brazil. “He has a more developmentalist agenda, while she has more of a sustainability agenda.”

Furthermore, Silva’s resentment went beyond political differences and accumulated losing battles. One of her most notorious grievances with the Workers’ Party occurred in the 2014 elections, when former president Dilma Rousseff was seeking re-election and waged a heavy campaign against her.

In the second round of those elections, Marina supported the right-wing candidate, Aécio Neves, ahead of Rousseff. Then in 2016, she also supported Rousseff’s impeachment. Even in 2018, in the second-round contest between Workers’ Party candidate Fernando Haddad and far-right Jair Bolsonaro, Marina resisted speaking out in favour of her former party, eventually expressing her intention to lend a “critical vote” to Haddad.

Today, political analysts see the 2018 victory of the far right and Bolsonaro’s anti-establishment discourse as a process in which the impeachment of the former president played a role. Asked whether she regretted not throwing stronger support behind the Workers’ Party, Silva is ambivalent: “The context that we had was one where political choices had to be made, and they were made in light of the facts that were laid out there.”

Brazil will lead by example again, it will assume leadership in the international environmental agenda

Even if past resentments remain present, with their September reconciliation, the politicians decided to look forward. “It was a really pragmatic reunion, and has been very welcomed,” Unterstell said. “It touches people’s minds and hearts.”

Marina Silva has since been putting her influence at the disposal of the Workers’ Party campaign. The weekend before the first round of the elections, she stood onstage with Lula in São Paulo, and now has volunteered to talk to politicians and voters on behalf of the former president.

In our interview, she was confident in her conclusion: “Brazil will lead by example again, it will assume leadership in the international environmental agenda, and give its best contribution.”