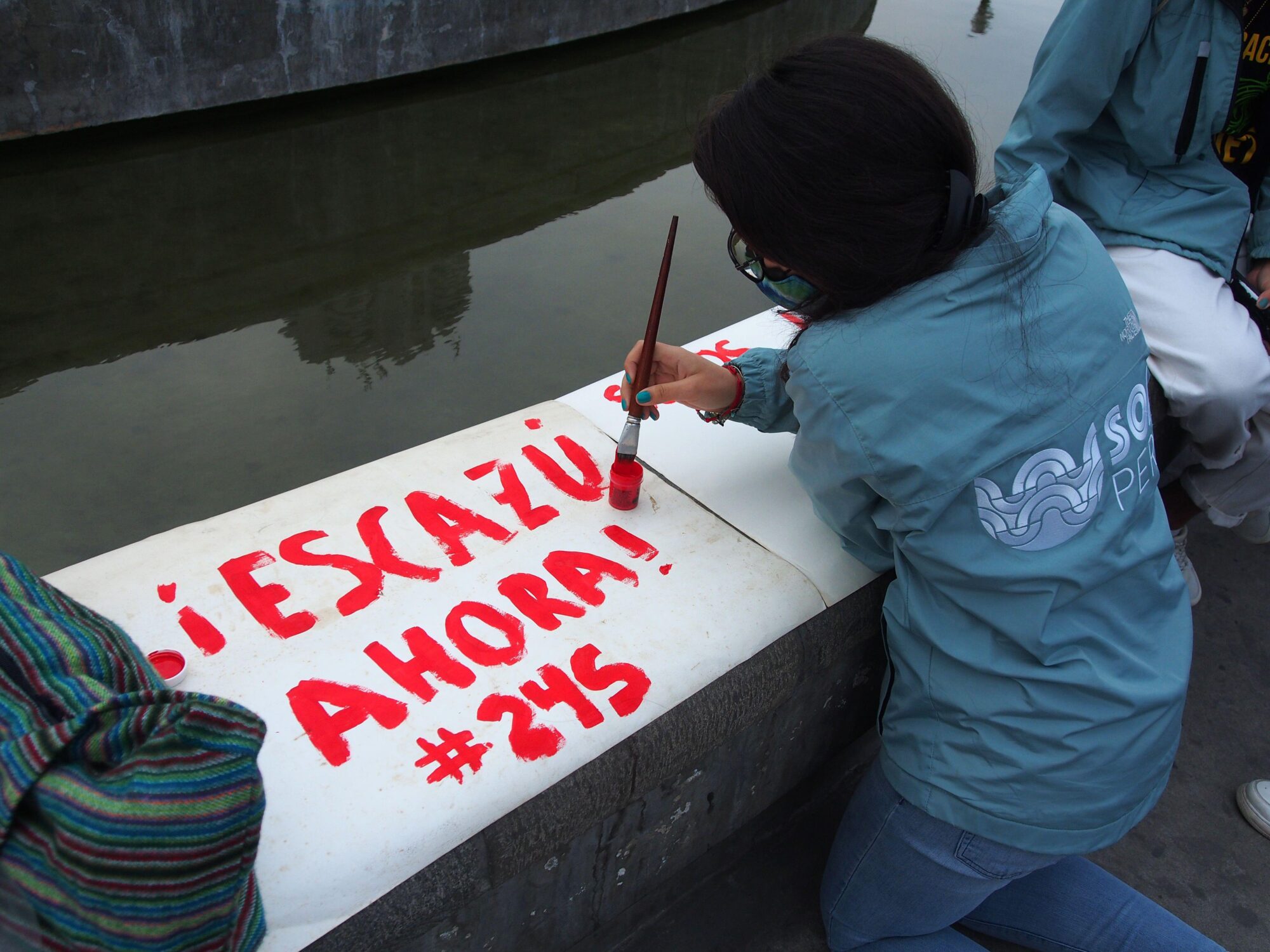

The Escazú Agreement, the first regional environmental agreement in Latin America and the Caribbean, will hold its first summit of parties (COP1) in the Chilean capital Santiago from 20-22 April. Representatives of governments and civil society will seek to advance the implementation of the agreement and secure its ratification by other signatory countries.

12

Latin American countries have ratified the Escazú Agreement, while a further 11 have signed but have either not presented a ratification bill to congress, or congress has not ratified it.

Escazú was approved in 2018 by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) after a six-year negotiation process. It entered into force in 2021 and, to date, a group of 12 countries have already signed and ratified it, while ratification by another 11 remains pending. Among them are Chile, Peru and Colombia.

The agreement seeks to guarantee the “full and effective” implementation of the rights of access to environmental information, public participation and justice, protecting citizens’ prerogative to live in a healthy environment. In 2020, more environmental defenders were killed in Latin America than any other continent.

The summit will be technical in its focus, concentrating on three articles included in the agreement: the rules for the implementation of the agreement, which includes the process for meaningful public participation; the funding necessary for the functioning and implementation of the agreement; and the establishment of an Implementation and Compliance Support Committee.

For Natalia Gómez, a member of EarthRights International and one of the six public representatives for the Escazú Agreement, the article organised by the Support Committee is one of the key issues to be discussed at the event.

“The heart of Escazú is the committee. It ensures accountability that this is not just about countries going and signing Escazú and getting a nice picture taken for the news, but that these obligations that are taken at the international level are really enforceable at the national level and are implemented,” she said.

Escazú Agreement: Active citizen participation

One of the most striking aspects of Escazú’s COP1 is the opportunity for citizens to participate. This distinguishes the summit from practices common in other international environmental and climate meetings, where only official representatives of party states participate.

The six participating public representatives were elected through an open vote organised by ECLAC. Most are socio-environmental activists or members of organisations working on transparency and environmental democracy. Chilean Andrea Sanhueza, director of the think tank Espacio Público, who has been actively involved in the Escazú process, is one of them.

“We met in 2012 as part of a global network to talk about what our goal was,” she said. “From there, we came up with the idea of pushing for agreements in different regions on principle 10 of the Rio Declaration, which refers to access to information and justice in environmental matters.”

Direct public participation has played an important role in the discussion processes, according to Gómez. “The public representatives seek to be a channel between civil society in general and the countries that sit at the negotiating table to channel their requests and comments,” she said.

Chile has always had an international policy of saying something and doing it…This was a complete break with this tradition

The meeting also affords the right to speak to anyone that registers to participate. For Andrea Sanhueza, this point has helped citizens to play a more active role in influencing the agreement.

The meeting is expected to make rapid progress, as partner countries have been working on drafts for months. In fact, a publicly broadcast Pre-Cop was held in early March, attended by states and public representatives.

Escazú Compliance Committee is key

The creation of an Implementation and Compliance Support Committee is one of the main issues to be worked on during the first COP. For Gómez, this article will generate considerable debate on the agreement.

“Escazú was finalised in 2018 and now states are going to negotiate the rules to implement some of the articles, mainly the COP, and how that conference will function. The one that seems the most important to me is the Implementation and Compliance Support Committee, which is article 18,” the environmental lawyer said.

Sanhueza believes that the creation of this committee and the methodology it will use will have important implications for citizens.

“This committee has to be created at the first COP. It is one of the most important things, because anyone, as a normal person, will have the right to go to this committee and write to it,” she said.

According to ECLAC’s schedule, on the first day of the event parties will present the actions taken so far. On Thursday 21 April, there will be a detailed discussion on the rules for the implementation of the agreement and the role of the Compliance Support Committee. Discussions on financing the agreement will be held on Friday 22, Earth Day, which will also be commemorated.

Chile and Colombia, awaiting ratification

The Escazú Agreement’s signatory countries fall into three categories, depending on the phase of the ratification process they are in. This determines their level of participation. There are State Parties, Signatory countries and Observer countries.

Although the deadline for signing the agreement ended two years ago, any state in the region can now join and become a State Party once it ratifies the agreement. However, where before countries used to sign and ratify, today they must send an accession bill to their national congress, as Chile recently did following the inauguration of its new president Gabriel Boric.

The Chilean government’s relationship with the Escazú Agreement has been chequered. It began as one of its main architects, but u-turned within days of signing the agreement. The foreign ministry claimed it would cause “inconveniences for Chile”.

Sanhueza took part in the first negotiations and recalls the abrupt change of heart.

“The case of Chile was very sad, it had a lot of leadership. I worked with it all these years. Several of us believe that this also slowed down progress in other countries,” she said, adding; “Chile has always had an international policy of saying something and doing it. And when it refuses, it does so with strong arguments. This was a complete break with this tradition.”

According to the National Institute of Human Rights (INDH), there are 128 socio-environmental conflicts in Chile, spread across all its regions. 85% of these conflicts affect the human right to live in a pollution-free environment. While 30% of these conflicts directly affect the right to indigenous participation and consultation.

In this context, Chile is drafting a new constitution, which the public will vote on in September. One of those in charge of writing the new magna carta is César Uribe, an environmental activist and convention member for electoral district 19, which encompasses a number of towns in southern Chile.

“The main reason I became a constituent is because of the socio-environmental struggle we have in Ñuble, in relation to the defence of the river, the defence of the mountain territory,” said Uribe. “We are going to be the second country in the world, after Ecuador, where rights to nature are established, which means more protection, which is positive.”

Like Chile, Colombia sent a bill to Congress on Escazú in the midst of multiple social demonstrations. National dialogues were organised so that citizens could express their views. Gómez said that the dialogues resulted in the express request to sign the Escazú agreement, to which the government committed.

Colombia was invited to Escazú COP1 as a signatory but the participation of the country, which is preparing for first round presidential elections on May 29, has yet to be confirmed.

For Gómez, there is a contradiction in Colombia’s stance. “The president promises to sign it and to send the bill to Congress with a message of urgency, and then his own party sinks the bill,” she said.