Negotiations for a treaty on the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity in the high seas have ended without conclusion at the UN headquarters in New York.

The fourth and final scheduled round of talks, which finished late on Friday 18 March, was supposed to conclude a multi-year process and result in a treaty. Now, governments will have to keep making progress in the coming months until another round of talks, likely to happen in August.

“We have not come to the end of our work,” said conference president Rena Lee, noting that Covid had caused major delays to the negotiations. “I believe that with continued commitment, determination and dedication, we will be able to build bridges and close the remaining gaps.”

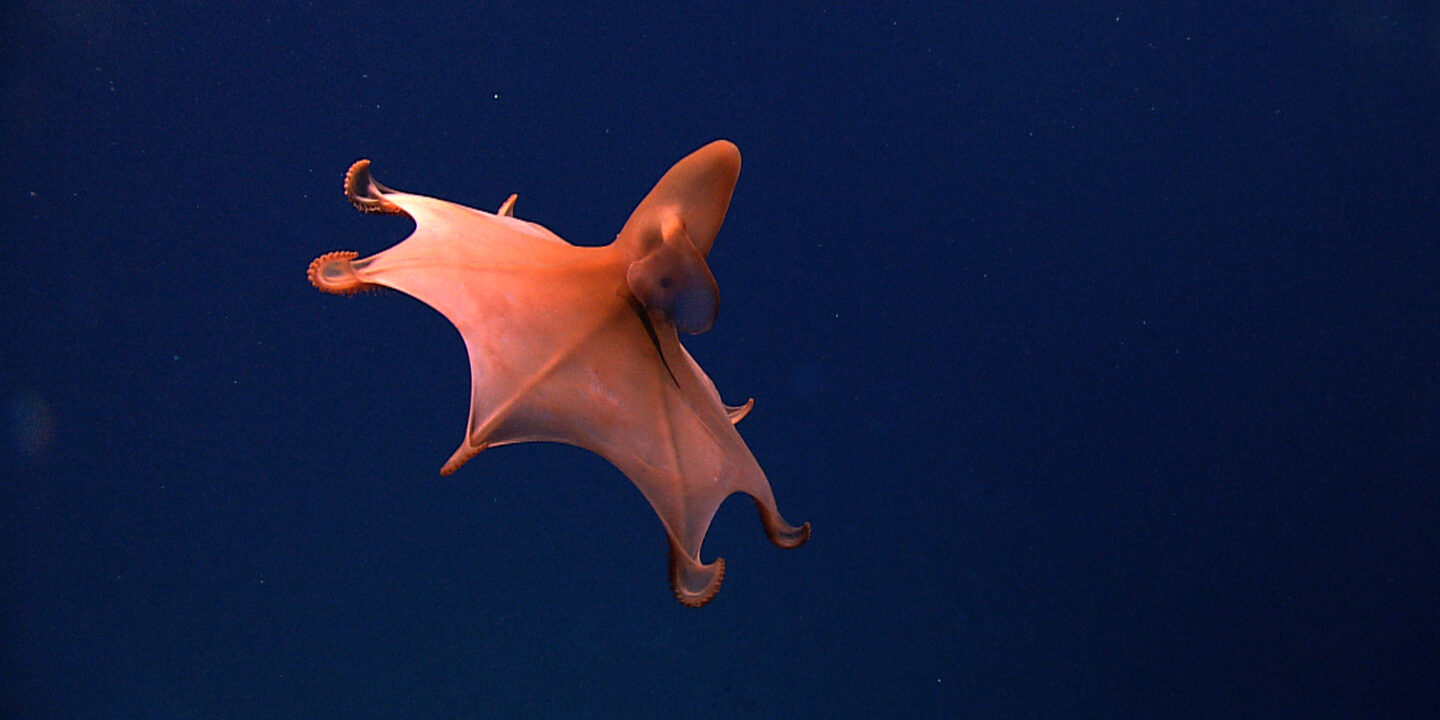

The high seas represent nearly two-thirds of the global ocean – but only 1% of them are currently fully protected. Outside nations’ exclusive economic zones, these remote areas support diverse ecosystems important for the health of the planet.

There has been a strong drive to get them protected, with 85 countries now part of the 30×30 coalition. Launched in January 2021, it aims to protect 30% of the planet’s land and sea by 2030. Without a high seas agreement, these pledges won’t have a legal basis in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Currently, countries can navigate, fish and carry out research on the high seas with few restrictions.

“All efforts must be devoted in the coming months to secure this long-awaited treaty in 2022 – a goal expressed by many governments,” said Peggy Kalas, director of the High Seas Alliance. “It was a very productive session but we don’t have an agreement yet. The high-level political momentum has to be translated into action.”

High time for a treaty?

Negotiations on the treaty began in 2018 after a decade of discussions at the UN. A so-called High Ambition Coalition of European Union nations and 13 other countries have endorsed the goal of concluding the process this year. Campaigners believe this is feasible but only if negotiations actively continue between now and the next round of talks.

Elizabeth Karan, who leads Pew’s high seas programme, said circumstances around the meeting signalled early on that it was not going to be the final one. Due to Covid, a reduced number of negotiators and campaigners were allowed to enter the UN building, which closed its doors at 6pm every day, not allowing for any extra time.

Karan said that despite negotiators running out of time, she had heard “a chorus of voices committed to finish the agreement and do hard work between now and the final meeting. Countries are trying to find common ground and bridge the gaps between their positions.”

The latest round of negotiations focused on the four key components of the future treaty: marine genetic resources; area-based management tools, like marine protected areas; environmental impact assessments; and capacity-building and the transfer of technology from richer to poorer nations.

There’s a lack of coherence between positions at the UN and how governments act at other bodies

Sharing the benefits of genetic resources is a particularly sensitive area for countries. It’s still not clear whether it will be mandatory or voluntary and whether it will include both monetary and non-monetary benefits. However, on regulations for marine protected areas and other area-based management tools, progress was made, such as on site selection criteria.

The process for impact assessments is also yet to be finalised, with no consensus on the applicable thresholds and criteria. Negotiators from developing countries are asking for stronger commitments on capacity building and technology transfer, for example with a compulsory environmental assessment mechanism.

“There was some progress. We saw some regional groups with progressive stands. However, there were also some countries defending the status quo, such as Russia. They see this treaty as having a coordination role without decision-making power,” said Veronica Frank, policy advisor at Greenpeace, referring to decision-making continuing to be the remit of those organisations that already manage the high seas.

Negotiations also have to agree on the institutional arrangements of a future treaty, which are critical for its effectiveness. Some of the issues include the mandate and rules of a regular conference of the parties (COP) – in the same UN vein as those that take place annually on climate and biannually on biodiversity – financing mechanisms and coordination with existing instruments regulating activities on the high seas.

“There’s a lack of coherence between positions at the UN and how governments act at other bodies. Here we talked about a new treaty, and this week the International Seabed Authority is meeting to talk about regulations for deep sea mining,” said Kristina Gjerde, IUCN high seas advisor. “That’s the biggest challenge of this new treaty, to ensure coherence.”

The road ahead

In their closing remarks, all delegations thanked conference president Lee for her efforts to make the meeting happen amid the pandemic. Many said they were hopeful that the next negotiating round will finally bring the treaty into existence. A new draft text is expected to be circulated by early May.

The EU delegation said “good progress” was made, and that they are optimistic about concluding the deal at the next meeting. Meanwhile, the Pakistani delegation, on behalf of the Group of 77 and China, said the commitment of all delegates is clear but asked for the principles of fairness and equity to be reflected in the agreement.

The ocean is high on the agenda this year, creating further pressure to finalise an agreement. The UN will host its Ocean Conference in Lisbon in June, while the World Trade Organisation (WTO) is expected to agree on ending fishing subsidies in the same month. A new global biodiversity framework is also in the works.

“We reached the point we wanted, having delegates engaged in real text-based discussions. Now, we need political impetus to make the deal happen,” Torsten Thiele, founder of the Global Ocean Trust, said.